EO Recital: Monteverdi Madrigals

20 NOV 2022, 6:00PM

EO Recital: Monteverdi Madrigals 2022

MONTEVERDI

20 NOV 2022, 6:00PM

St Margaret's Church, Putney

Poppy Shotts, Helen May – soprano

Nathan Mercieca - countertenor

John Twitchen – tenor

Marcio Da Silva – baritone

Cédric Meyer – lute

Predrag Gosta - harpsichord

Paul Jenkins - recorder

Marcio da Silva, Helen May - recorders

Programme

Gira Il Nemico (Book 8)

Mentre Vaga Angioletta (Book 8)

Dolcissimo uscignolo (Book 8)

Chi vol haver Felice (Book 8)

Perche t’en fuggi o fillide (Book 8)

Su su Pastorelli Vezzosi (Book 8)

O come sei gentile (Book 7)

Romanesca a due voci (Book 7)

Tirsi e Clori (Book 7)

Amor che deggio far (Book 7)

Claudio Monteverdi.

Claudio Monteverdi was born in Cremona in 1567, a city which soon achieved fame as a centre of instrument making as the home of both the Amati and Stradivari families. As a young man Monteverdi studied with Marc'Antonio Ingegneri, Maestro di Capella at the Cathedral in Cremona. Ingegneri published eight books of madrigals himself (as well as sacred music) and when his teenage pupil came to write his own secular part-songs, it was only natural that the work of his teacher initially served as his model.

To the English a madrigal is a catch-all term which covers a multitude of different forms, such as the canzonet, ballata, chanson, and many local variations on these, as well as the madrigal itself. The English ear tends to expect madrigals to be in the Elizabethan mode - full of bright, happy sentiments and plenty of fa la las. Monteverdi’s madrigals are far removed from this. His eight books of madrigals took more than half a century to create. The earliest were written at the onset of his composing career when he was a mere teenager. At this point he had grand ideas but was a beginner in terms of his writing skills. The later madrigals were written when he was an established master, writing music that is striking in its innovation. Taken together the books include over ten hours of music, and they constitute something of a musical diary of Monteverdi's development as a composer from his teens to his 70s.

This concert focuses on pieces from the Seventh and Eighth Books, but to fully appreciate these it is useful to have some understanding of Monteverdi's madrigal composition journey.

The Madrigals.

Monteverdi’s First Book of Madrigals was printed on New Year’s Day 1587, when he was just 19 years old. This was a substantial statement to the world: a collection of 17 pieces for unaccompanied voices in five parts. Only about one third of the texts are in the pastoral tradition, telling of playful nymphs and shepherds loving and deserting each other and describing their laughter or tears as required. The remaining texts allowed Monteverdi to probe more deeply into darker texts, creating new sounds to express varied emotions. These more personal texts are about real people who are in love, but rarely happily. Words like mora (die), and phrases like l'aspro martire (bitter torment), are common - love unrequited and rejected more often than love fulfilled and enjoyed.

Monteverdi's Second Book of Madrigals was published on New Year’s Day 1590. The 21 pieces in this collection show his continued development in terms of balancing musical interest, illustration of the text, and sheer audacity of ideas. Musicologists have suggested that what Monteverdi was developing here was ‘musical mannerism’ - the aural expression of the style of art seen from the middle of the 16th century in Tintoretto and late Michelangelo. The yearning, twisting forms of mannerist art (Michelangelo's 1541 Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel) grew into the more yearning and twisting forms of Baroque art (Bernini’s 1622 sculptures of Apollo and Daphne), and a similar thing happened in music. Monteverdi took the musical love child of the Renaissance - the madrigal - and made it twist and turn and emote and evoke and yearn and desire more and more with every publication.

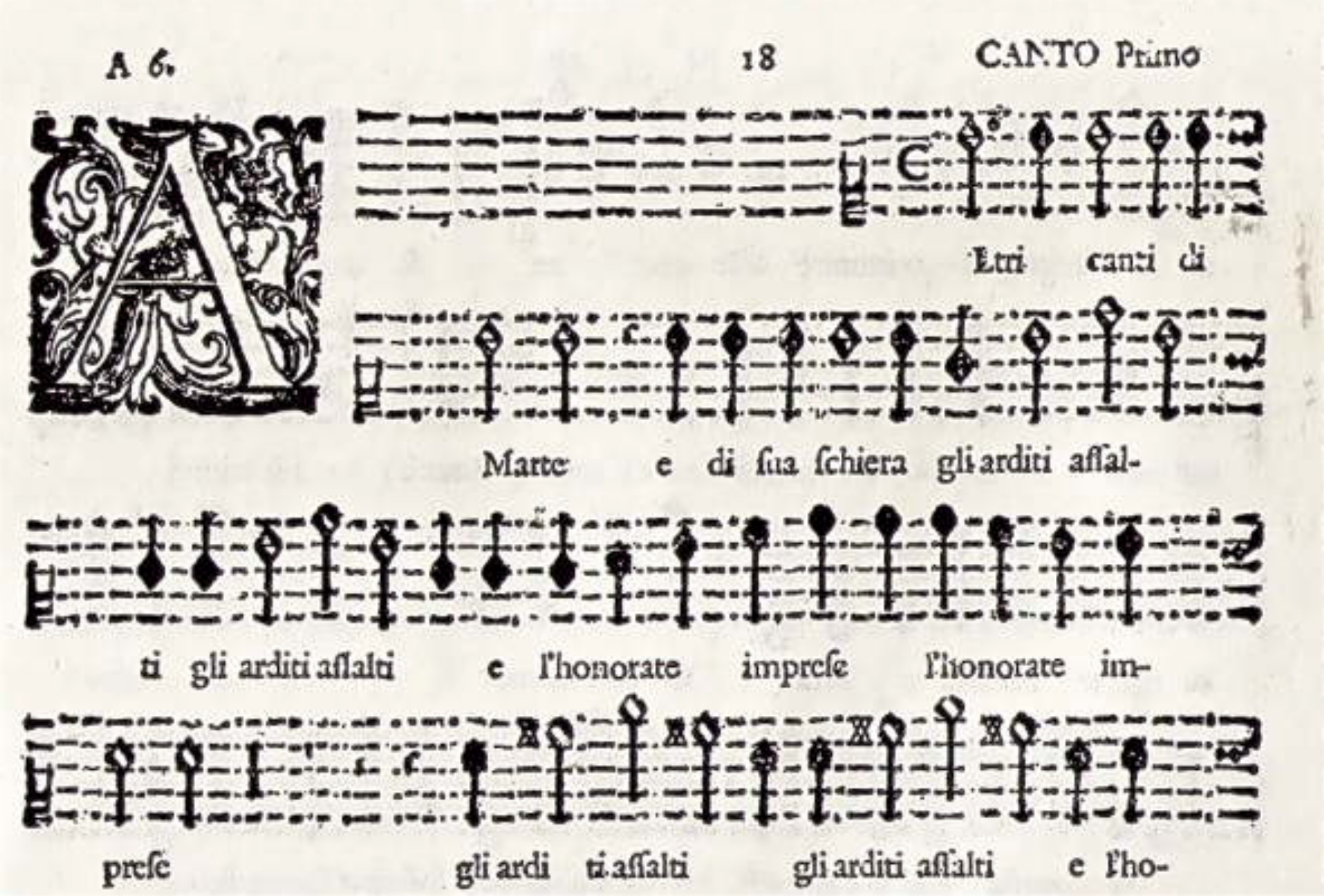

Manuscript detail from the Canto Primo part, of Claudio Monteverdi Madrigals Libro VIII. Bibliotheca Musica Bononiensis, Line-cut of Venice, 1638 edition.

The Third Book of Madrigals, was published in 1592 when Monteverdi was 25, not long after his arrival in Mantua to take up his first major job at the Gonzaga court. It bears evidence of the influence of Mantua’s Director of Music, the renowned Flemish-born composer Giaches de Wert, as well as Monteverdi's own growing technique and confidence. This book contains 20 madrigals for five voices. Unlike the earlier publications, which contain music that could be sung by good amateurs at home, these are virtuoso pieces designed to be performed by professionals for an audience. Here there are examples of the playful and pastoral, but also unexpected discords, harmonies of searching depth, unusual voice couplings, and changes of pace to convey erotic desire, melancholy, and love and death (death both real and sexual). Many thought he had gone too far. In 1600, Monteverdi was targeted in a publication written by a monk living in Bologna called Giovanni Maria Artusi who criticised Monteverdi for his dissonances and lapses in taste.

However, when Monteverdi's Fourth Book of Madrigals appeared in print in 1603, he seemed ready to go even further. In the 20 madrigals in this book Monteverdi entered a new musical world of expressive power. His attention to textual detail is matched by an equal attention to overall sound and architectural balance. This book contains pieces which seem to inhabit a more cerebral, spiritual realm. He continued to play wickedly with the harmonies and erotic ambiguities of sighing and dying, but the obsession with death goes far beyond any titillating connection with sex. Love is likened to war, and Monteverdi seems to embrace the static, angst-ridden otherworldliness of his contemporary Carlo Gesualdo as he explores the musical tensions of a suffering soul living, and dying, in an inferno of eternal grief. The transformation from the 17-year-old talented writer of light love songs to the 34-year-old composer of music of enormous intellectual and emotional depth is astonishing. This is a long way from Morley’s ‘Now is the month of Maying’!

In 1605, with the publication of the Fifth Book of Madrigals, Monteverdi made it clear that he had no intention of going back to older, purer, more correct styles. The fifth book deals with Monteverdi's consuming passion, namely, the interaction of text and music so that the listener is moved and affected. It also contains a major departure from Monteverdi's past madrigals and those of all other madrigal composers: it allows the use of instruments.

In the preface to the edition, Monteverdi boldly stated his artistic intentions. He describes two distinct practices of composition. The prima prattica or ‘first practice’, is the old style as exemplified by the rules and restraint of the high Renaissance (Palestrina). In this style the words are subservient to the music. The seconda prattica or ‘second practice’ is the new style - Monteverdi's style - which seeks to restore to music the emotive power written about by the ancient Greeks, even if this means breaking the rules, allowing unprecedented dissonance, and the adding of instruments to vocal forms which had hitherto been performed a cappella. In this style the music is subservient to the words.

The fifth book is arguably the centre point of Monteverdi's creative career, and every one of its 19 madrigals show his obsession with reflecting every subtle variation of the text in the music. This extends to the way in which the pieces are arranged. The pieces fall into four groups, each of which is a self-contained dramatic unit. As a result, sections of the book sound remarkably like opera. The composition of Monteverdi's first opera, Orfeo, was only two years later and in many ways this book is a practice run for that ground-breaking masterwork.

The Sixth Book of Madrigals was published in 1614, the year after he had moved to Venice, but most of its 18 pieces would have been written over the preceding few years in Mantua. This book is obsessed with separation, departure, and loss. It is the only one of Monteverdi's madrigal books published without a dedication, suggesting that the volume has more of a personal than a professional impetus. The composer's wife, Claudia, had died in 1607, and in 1608 his pupil and friend, the singer Caterina Martinelli, also died. The emotions here are raw and real. Apart from the bereavements, Monteverdi in his final years at Mantua, was exhausted and feeling trapped.

This book contains Monteverdi's last a cappella madrigals. Most use continuo accompaniment, making the operatic separation of one or two voices easier and thus providing a more varied musical palette for Monteverdi’s emotional painting. However, by the time of its publication the classic five-voice madrigal was becoming a rather old-fashioned form. Monteverdi had kept it fresh with new and daring harmonies and with the addition of continuo it was able to straddle the world of opera more readily, but still, the basic format was a five-voice part-song. With the end of his own personal anguish in Mantua and the start of a much happier time in Venice, such overwrought emotional content seemed less relevant.

It is perhaps no surprise therefore that the Seventh Book of Madrigals was very different. It was published in 1619, five years after the sixth, when Monteverdi was 52. It is remarkable for the sheer variety of genres and styles it contains, with the old and the new side by side, music for solo voice, duets, trios, dramatic scenes, and - at the end - a complete ballet for voices and instruments, Tirsi e Clori, which had been written in 1615 for the Duke of Mantua. In addition to continuo instruments there are parts for violins and gambas, and even an opening sinfonia. This book is huge - twice the length of the preceding madrigal publications - comprising 29 separate pieces. The definition of madrigal has been stretched beyond all recognition. In fact, Monteverdi titled the seventh book ‘Concerto’, a term used in his day to mean music which combined voices with instruments. Once again Monteverdi is concerned above all with the clarity and expression of the text. There are still a few examples of the dark angst of the Mantuan madrigals, but overall, the mood is lighter. The inclusion of obbligato instruments in some pieces - over and above the continuo - creates an entirely new sound world.

The Eighth Book of Madrigals, published in 1638 when Monteverdi was 71, was an even grander, more varied, and more spectacular publication than the seventh. It was published under the title of Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi (Madrigals of war and love). Apart from part-songs and ensembles the publication contains a ballet (the Ballo delle ingrate or Ballet of the Ungrateful Women) and a miniature opera (The Battle of Tancred and Clorinda), as well as smaller-scale pieces full of rhythmic life and vigour designed to be danced to as well as sung. The ‘war and love’ of the title reflects the fact that some of the pieces refer to war as an allegory of love's battles, and vice versa. The whole collection embodies what Monteverdi referred to as his stile concitato or ‘agitated style’. This book is a compendium of his work spanning three decades and shows Monteverdi at the peak of his compositional creativity and innovation and in complete control of all aspects of his technique.